|

|

In

spite of much rhetoric to the contrary, the United States’ coastal waters

are rich in fisheries resources. While stocks of New England cod, haddock

and yellowtail flounder - collectively referred to as “groundfish” - are

currently depressed relative to former periods of high abundance, fisheries

experts believe they have been replaced by equivalent amounts of other

species such as dogfish and skates. Happily, due to a combination of stringent

management measures and natural population processes, the majority of the

groundfish stocks are now in the process of rebuilding.

In

spite of much rhetoric to the contrary, the United States’ coastal waters

are rich in fisheries resources. While stocks of New England cod, haddock

and yellowtail flounder - collectively referred to as “groundfish” - are

currently depressed relative to former periods of high abundance, fisheries

experts believe they have been replaced by equivalent amounts of other

species such as dogfish and skates. Happily, due to a combination of stringent

management measures and natural population processes, the majority of the

groundfish stocks are now in the process of rebuilding.

The waters off the Mid-Atlantic and New England are currently home to several millions of tons of Atlantic mackerel and herring. (Exactly how many tons is a matter of some debate. Fish populations are estimated using complex statistical manipulations that don’t always enjoy universal acceptance. For purposes of scale, the total weight of all the edible fish and shellfish commercially caught in 1995 from Maine to Florida was under a million tons.) Similarly, the menhaden fishery, which has been a stable source of protein-rich fish meal, fish oil and sports fishing bait for over a century, is supported by a tremendous mass of fish ranging from the Gulf of Mexico to New England. Many other species of fish and shellfish are available at high levels of abundance.

Unfortunately, some of these species - in many instances the most common - aren’t compatible with the culinary preferences of the U.S. seafood consumer. Much of the domestic seafood demand is for processed tuna, fresh or frozen shrimp and mild-tasting, white-fleshed fish like flounder, cod and striped bass. Conversely much of the international demand is for species unpopular with U.S. consumers but common and readily available to U.S. commercial harvesters in our inshore and offshore waters. These include herring, mackerel, dogfish and squid.

In recognition of this disparity between the fish available in our waters and the seafood preferences of our consumers, one of the goals of the Magnuson Act, the controlling Federal fisheries law which was enacted in 1976, was to replace the foreign catcher/processor fleets that were harvesting these high-demand (in international markets) species with U.S. boats and shore-based processing facilities. Another priority set forth in the Act was the development of foreign markets for the products the revitalized U.S. commercial fishing industry was producing (see the following page).

This was one of the more successful aspects of

domestic commercial fisheries policy in the two decades following the passage

of the Magnuson Act. From a primarily small-boat fleet fishing near-shore

waters and for the most part supplying local or regional markets, the domestic

commercial fishing industry has evolved into one employing state-of-the-art,

ocean-spanning vessels providing competitively priced seafood to global

markets. The positive impacts of this globalization have extended far beyond

the fishermen, processors, dealers and consumers that have benefitted directly

from it.

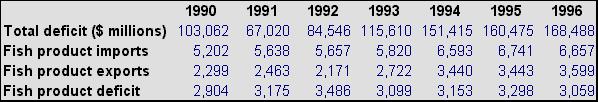

As the table above (from the U.S.D.O.C. Web Site www.ita.doc.gov/industry/otea/otea.html - U.S. Aggregate Foreign Trade Data: Tables 23, 24 and 25) illustrates, the U.S. trade deficit ranged from $70 billion to $170 billion in the period from 1990 to 1996. In that time annual seafood imports exceeded exports by from $2.2 to $3.6 billion dollars, accounting for approximately two percent to four percent of the total deficit each year.

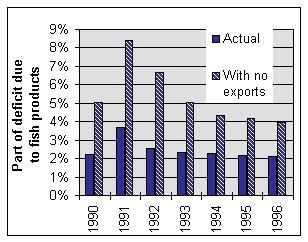

The graph to the left contrasts the actual trade

deficit due to fishery products with what that deficit would have been

in the absence of any fishery exports. It illustrates how the U.S. fishing

industry’s increasing focus on products with strong overseas demand and

increasing capability to catch, process and sell those products has had

a significant impact on holding down the deficit. If it weren’t for the

export of fishery products in 1991, for example, the deficit would have

risen from $67 billion to over $70 billion, an increase of four percent.

The graph to the left contrasts the actual trade

deficit due to fishery products with what that deficit would have been

in the absence of any fishery exports. It illustrates how the U.S. fishing

industry’s increasing focus on products with strong overseas demand and

increasing capability to catch, process and sell those products has had

a significant impact on holding down the deficit. If it weren’t for the

export of fishery products in 1991, for example, the deficit would have

risen from $67 billion to over $70 billion, an increase of four percent.

While not receiving the attention that other manufactured

goods or commodities do, fishery products have a far from trivial impact

on our balance of trade. The harvest of fish and shellfish from our rich

coastal waters, whether to satisfy domestic demand or to supply foreign

markets, is extremely important to our national economy and that importance

is all too often overlooked by our policy makers and the management establishment.

The 1970s showed a gradual increase in consumption to above the 13 pound level. Then, starting in 1980, pushed by an upsurge in health consciousness, research demonstrating the dietary benefits of seafood consumption and the easy availability of high quality domestic seafood products, average consumption rose to above 16 pounds in 1988. It has remained around 15 pounds per person since then. |

| When the Congress of the United

States passed the Magnuson Act in 1976, and as it has been amended since,

the intent was and continues to be to maximize the benefits gained by U.S.

citizens from the utilization of the living marine resources of the U.S.

Exclusive Economic Zone and adjacent waters through:

• Assuring the sustainability

of the U.S. fisheries for future generations through identifying and preserving

(or restoring) essential habitat and effectively managing recreational

and commercial harvesting “...for the conservation and management of the

fishery resources of the United States is necessary to prevent overfishing,

to rebuild overfished stocks, to insure conservation, to facilitate long-term

protection of essential fish habitats, and to realize the full potential

of the Nation's fishery resources.”

In spite of the positive effects that the high level of fish and shellfish export activity has had on the trade deficit - and the obvious beneficial impacts of these exports on the overall economy - a handful of anti-commercial fishing groups are now actively campaigning against the harvest of fishery products from U.S. waters if those products are bound for foreign markets. They seem to be arguing that the purpose of the Magnuson Act was to “reserve United States’ fish for United States’ citizens” and that exporting “our fish” is somehow counter to the public good. Our perusal of the Act hasn’t shown where this is either stated or implied. In fact, as illustrated above, the Act not only allows for but actually encourages the export of fishery products. The above quotations were taken from the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Public Law 94-265 As amended through October 11, 1996 - J.Feder version 12/19/96) |