Issue #3

June 10, 1997

Trends in and methods of commercial

fishing

Issue #3

June 10, 1997

Trends in and methods of commercial

fishing

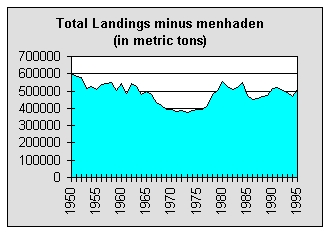

As

the chart from the NMFS website [

As

the chart from the NMFS website [ ]shows,

East coast commercial landings have declined substantially since 1950.

While due to a number of interrelated factors, the decline is in large

part because all major East coast fisheries are now managed by state or

federal agencies. While fisheries were for the most part “wide open” prior

to passage of the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act in

1976, commercial harvesters in particular have been subjected to increasing

controls on how, where and when they can fish and on what they can catch

since then. There are also greater restrictions on who can fish. While

the methods of commercial harvesting today - some of which are described

below - have been in use for generations, management measures and an increasing

awareness on the part of the fishermen that the ocean isn’t an endless

source of fresh seafood have combined to make commercial harvesting much

more selective than it was even a decade ago. The result is that fewer

fish are being harvested, and they are being harvested in a much more sustainable

manner.

]shows,

East coast commercial landings have declined substantially since 1950.

While due to a number of interrelated factors, the decline is in large

part because all major East coast fisheries are now managed by state or

federal agencies. While fisheries were for the most part “wide open” prior

to passage of the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act in

1976, commercial harvesters in particular have been subjected to increasing

controls on how, where and when they can fish and on what they can catch

since then. There are also greater restrictions on who can fish. While

the methods of commercial harvesting today - some of which are described

below - have been in use for generations, management measures and an increasing

awareness on the part of the fishermen that the ocean isn’t an endless

source of fresh seafood have combined to make commercial harvesting much

more selective than it was even a decade ago. The result is that fewer

fish are being harvested, and they are being harvested in a much more sustainable

manner.

Otter Trawling

[ ]-

Otter trawling is one of the oldest of New Jersey’s traditional net fisheries.

A boat, ranging in size from 40 to 100 plus feet in length depending on

the fishery, tows a funnel-shaped net through the water, herding the quarry

into a closed-off bag, commonly called a “cod end.” After a tow of up to

several hours the net is brought back to the boat and the catch, after

being spilled from the cod end, is sorted, cleaned and packed on ice or

in brine for the return to the dock. The sorting is necessary because in

this and most other commercial fisheries non-targeted species are taken

as well. These non-targeted species, collectively known as “by-catch” and

occasionally caught in relatively high numbers, are avoided by fishermen

whenever possible, representing wasted effort and added expense (and often

no economic return). Major research initiatives to eliminate bycatch or

to develop markets for it are ongoing in the otter trawl and other fisheries.

Trawls can be operated on the bottom or higher up in the water column.

Some of the primary species sought in the mid-Atlantic by trawlers are

silver hake, fluke, flounder, mackerel, squid and weakfish.

]-

Otter trawling is one of the oldest of New Jersey’s traditional net fisheries.

A boat, ranging in size from 40 to 100 plus feet in length depending on

the fishery, tows a funnel-shaped net through the water, herding the quarry

into a closed-off bag, commonly called a “cod end.” After a tow of up to

several hours the net is brought back to the boat and the catch, after

being spilled from the cod end, is sorted, cleaned and packed on ice or

in brine for the return to the dock. The sorting is necessary because in

this and most other commercial fisheries non-targeted species are taken

as well. These non-targeted species, collectively known as “by-catch” and

occasionally caught in relatively high numbers, are avoided by fishermen

whenever possible, representing wasted effort and added expense (and often

no economic return). Major research initiatives to eliminate bycatch or

to develop markets for it are ongoing in the otter trawl and other fisheries.

Trawls can be operated on the bottom or higher up in the water column.

Some of the primary species sought in the mid-Atlantic by trawlers are

silver hake, fluke, flounder, mackerel, squid and weakfish.

Trawling is regulated through limiting entry into

particular fisheries, closed areas and/or seasons and by mesh requirements

in the whole net or in the cod end.

Scallop dredging

- The majority of scallops landed on the East coast are caught with scallop

dredges, large steel constructions that are towed across the bottom, “scraping”

up the scallops that are found there. The dredge consists of a rigid forward

framework behind which is attached a bag made of steel rings. After a tow

the dredge is hauled on board, the bag emptied and the catch sorted. Usually

the scallops are shucked on board, the white muscles that consumers in

the U.S. know as scallops being retained and the shell and other waste

being returned to the ocean. However, a small but growing market exists

for scallops “in-the-shell” and boats will sometimes keep part of the catch

unshucked to supply it.

Scallop fishing is managed by entry limits, closed

seasons and minimum size via the diameter of the rings in the bag.

Hydraulic Dredging

[ ]-

Hydraulic dredges are similar to the mechanical dredges used by scallopers

with one modification. A manifold is mounted on the front of the dredge

with nozzles directed downwards. Water from a pump on the dredge boat is

ejected from the nozzles at high pressure, stirring up and “fluidizing”

the sand in front of the dredge and allowing it to capture the clams that

normally burrow in the bottom. The two mid-Atlantic species sought by hydraulic

dredge boats are surf clams and ocean quohogs.

]-

Hydraulic dredges are similar to the mechanical dredges used by scallopers

with one modification. A manifold is mounted on the front of the dredge

with nozzles directed downwards. Water from a pump on the dredge boat is

ejected from the nozzles at high pressure, stirring up and “fluidizing”

the sand in front of the dredge and allowing it to capture the clams that

normally burrow in the bottom. The two mid-Atlantic species sought by hydraulic

dredge boats are surf clams and ocean quohogs.

The surf clam and ocean quohog fisheries are two

of the most “specialized” on the East coast, requiring vessels that aren’t

suited for any other fisheries and providing a product that has virtually

no demand when fresh and in the shell (these clams are used in clam strips,

in chowders, and in the many products requiring minced or chopped clams).

One of the most valuable cash crops harvested from New Jersey’s waters,

surf clams and ocean quohogs are the primary ingredient in canned and frozen

clam products sold worldwide.

The surf clam/ocean quohog fisheries are managed

through limits on the number of boats allowed to participate, gear restrictions

and strict quotas.

Longlining

[ ]-

This is a hook and line fishery in which baited hooks are suspended at

intervals from a horizontal “long line” which is hauled in after a set

period of time. The pelagic longline boats based in New Jersey harvest

tunas and swordfish in the upper part of the water column and fish anywhere

on our side of the North Atlantic. The boats in the directed (meaning they

fish exclusively for) shark fishery also use longlines on the surface,

generally closer in. Tilefish longline boats set their gear on the bottom

in the deeper waters of the continental shelf. Longline caught fish are

among the highest quality available due to the one-at-a-time handling characterizing

the fishery.

]-

This is a hook and line fishery in which baited hooks are suspended at

intervals from a horizontal “long line” which is hauled in after a set

period of time. The pelagic longline boats based in New Jersey harvest

tunas and swordfish in the upper part of the water column and fish anywhere

on our side of the North Atlantic. The boats in the directed (meaning they

fish exclusively for) shark fishery also use longlines on the surface,

generally closer in. Tilefish longline boats set their gear on the bottom

in the deeper waters of the continental shelf. Longline caught fish are

among the highest quality available due to the one-at-a-time handling characterizing

the fishery.

The longline fisheries are managed through a variety

of measures, primarily quotas, seasonal closures and limits on the number

of boats allowed to participate and, with several other fisheries, participate

in official on-board observer programs.

Gill netting

[ ]-

Sometimes confused with the huge open-ocean drift gillnets that were indicted

as indiscriminate killers of marine life several years back (and subsequently

banned in most waters), the inshore gillnetting fleet in New Jersey is

characterized by smaller boats making one day trips and landing limited

amounts of high quality products like weakfish, monkfish, shad and bluefish.

Gillnets are vertical panels of netting, suspended either at or under the

surface, that entangle the fish that swim into them. The fishermen periodically

haul the nets into the boat, removing the fish and returning the nets to

the water to continue fishing. The gillnet fishermen being familiar with

the migratory patterns of the fish the are seeking, this is a “clean” fishery.

]-

Sometimes confused with the huge open-ocean drift gillnets that were indicted

as indiscriminate killers of marine life several years back (and subsequently

banned in most waters), the inshore gillnetting fleet in New Jersey is

characterized by smaller boats making one day trips and landing limited

amounts of high quality products like weakfish, monkfish, shad and bluefish.

Gillnets are vertical panels of netting, suspended either at or under the

surface, that entangle the fish that swim into them. The fishermen periodically

haul the nets into the boat, removing the fish and returning the nets to

the water to continue fishing. The gillnet fishermen being familiar with

the migratory patterns of the fish the are seeking, this is a “clean” fishery.

Gillnet fisheries are managed through limited

entry, closed seasons, and net length and mesh restrictions.

Trap and pot fisheries

[ ]-

Several bottom-dwelling fish and shellfish species are harvested in wooden

or wire traps in New Jersey’s waters. Whether lobsters, crabs, whelks,

sea bass or tautog are the quarry, the traps work the same way. A large,

funnel-shaped opening allows the catch into the trap - either seeking bait

or shelter - but prevents it from getting back out. The traps range in

size from smaller crab pots used by baymen in New Jersey’s estuaries to

the large offshore lobster pots that are set in several hundreds of feet

of water offshore. Trap caught fish and shellfish are of the highest quality,

still alive when landed and often kept alive until bought by the consumer.

]-

Several bottom-dwelling fish and shellfish species are harvested in wooden

or wire traps in New Jersey’s waters. Whether lobsters, crabs, whelks,

sea bass or tautog are the quarry, the traps work the same way. A large,

funnel-shaped opening allows the catch into the trap - either seeking bait

or shelter - but prevents it from getting back out. The traps range in

size from smaller crab pots used by baymen in New Jersey’s estuaries to

the large offshore lobster pots that are set in several hundreds of feet

of water offshore. Trap caught fish and shellfish are of the highest quality,

still alive when landed and often kept alive until bought by the consumer.

The trap fishery is regulated through seasonal

and area closures and through the use of escape vents allowing immature

fish or shellfish to escape. To avoid so-called ghost fishing, where a

trap that is unavoidably lost by a fisherman lays on the bottom and continues

to trap fish or shellfish, traps must now have doors which automatically

open after being submerged for a certain time.

New Jersey FishNet is supported

by the Cape May Seafood Producer’s Association, The Family and Friends

of Commercial Fishermen, the Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative, Lund’s Fishery,

the National Fisheries Institute and Viking Village Dock

New Jersey FishNet is supported

by the Cape May Seafood Producer’s Association, The Family and Friends

of Commercial Fishermen, the Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative, Lund’s Fishery,

the National Fisheries Institute and Viking Village Dock

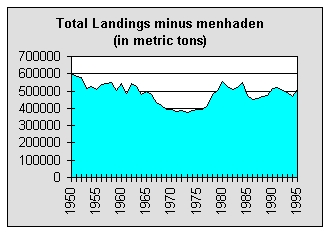

As

the chart from the NMFS website [

As

the chart from the NMFS website [![]() ]shows,

East coast commercial landings have declined substantially since 1950.

While due to a number of interrelated factors, the decline is in large

part because all major East coast fisheries are now managed by state or

federal agencies. While fisheries were for the most part “wide open” prior

to passage of the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act in

1976, commercial harvesters in particular have been subjected to increasing

controls on how, where and when they can fish and on what they can catch

since then. There are also greater restrictions on who can fish. While

the methods of commercial harvesting today - some of which are described

below - have been in use for generations, management measures and an increasing

awareness on the part of the fishermen that the ocean isn’t an endless

source of fresh seafood have combined to make commercial harvesting much

more selective than it was even a decade ago. The result is that fewer

fish are being harvested, and they are being harvested in a much more sustainable

manner.

]shows,

East coast commercial landings have declined substantially since 1950.

While due to a number of interrelated factors, the decline is in large

part because all major East coast fisheries are now managed by state or

federal agencies. While fisheries were for the most part “wide open” prior

to passage of the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act in

1976, commercial harvesters in particular have been subjected to increasing

controls on how, where and when they can fish and on what they can catch

since then. There are also greater restrictions on who can fish. While

the methods of commercial harvesting today - some of which are described

below - have been in use for generations, management measures and an increasing

awareness on the part of the fishermen that the ocean isn’t an endless

source of fresh seafood have combined to make commercial harvesting much

more selective than it was even a decade ago. The result is that fewer

fish are being harvested, and they are being harvested in a much more sustainable

manner.