|

| A drawing of an early steam-powered menhaden purse seiner from The Men All Singing. |

|

| A drawing of an early steam-powered menhaden purse seiner from The Men All Singing. |

|

|

| * In The Men All Singing (referenced below) Mr. Frye quoted G.B. Goode in an earlier book that menhaden were “a staple article of food among the people living on the sea-coast of New Jersey” and were “in good demand on the shores of Chesapeake Bay" and that in 1874 they were being sold in the Washington fish market at a price nearly as high as that of striped bass. |

For most of its long history the menhaden fishery has been plagued by periodic attempts of various groups to force it out of particular areas. These were sometimes aimed at the processing plants, which are not always considered the best of neighbors, and sometimes at the harvesting vessels, which are generally assumed to either catch “all the gamefish” in an area or “all the gamefish’s food” and forcing them to forage elsewhere. As a response to what must be these latter concerns, legislation has recently been introduced in the New Jersey Senate to drastically restrict menhaden fishing in state (out to three miles) waters.

In support of this legislation, materials purporting to be factual and

science-based have been circulating at yacht clubs, at sportsfishing shows

and in the legislature in Trenton. Unfortunately, those materials that

we have seen contain little or no documentation or explanation of the “facts”

they contain. They present what seem to be little more than anti-commercial

fishing sentiments as accepted science. The documented information we’ve

compiled here isn’t to refute any of the claims made by them. Rather, it

is material we hope will fill any gaps that our sportsfishing and yachting

colleagues might have somehow overlooked in their zeal to turn New Jersey’s

coastal waters into their own exclusive playground. We have every confidence

that anyone taking the time to objectively review what we’re presenting

will be capable of making an unbiased evaluation of the menhaden fishery

as it exists today and of the effectiveness of the existing menhaden management

system.

Of more recent vintage is the anti-menhaden harvesting argument that taking fish that are an important part of the marine food web will cause the predator species that eat them to either starve or to move to “greener pastures.” Again going to the literature, in 1977 in Menhaden, Sport Fish and Fishermen (in Marine Recreational Fisheries) researcher Candace A. Oviatt concludes “...even when menhaden abundances are so low that it is not commercially feasible to catch them they are still sufficiently abundant to be a primary food source for predatory fish.” Even more compelling than the literature, however, are the actual menhaden and sports fishing landings in New Jersey over the last ten years. As explained in the box on the previous page, there is no sign that the recreational landings of the species most likely to be impacted by a lack of menhaden are doing anything but thriving, with their combined landings increasing from year to year along with the menhaden harvest.

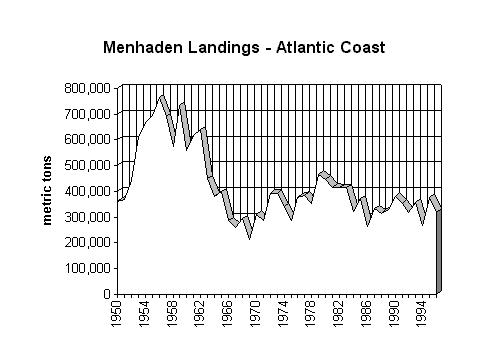

Finally, the anti-menhaden fishing groups and individuals would have us

believe that the menhaden fishery is currently undergoing an unprecedented

and potentially ecosystem-shattering period of expansion. As the chart

of Atlantic coast landings from 1950 to 1996 (

Finally, the anti-menhaden fishing groups and individuals would have us

believe that the menhaden fishery is currently undergoing an unprecedented

and potentially ecosystem-shattering period of expansion. As the chart

of Atlantic coast landings from 1950 to 1996 (![]() for

coastal landings data) illustrates, nothing could be farther from the truth.

In fact, coastal landings of menhaden today are barely half of what they

were in the middle Fifties, those “good old days” that so many of our recreational

fishing colleagues look back on nostalgically.

for

coastal landings data) illustrates, nothing could be farther from the truth.

In fact, coastal landings of menhaden today are barely half of what they

were in the middle Fifties, those “good old days” that so many of our recreational

fishing colleagues look back on nostalgically.

So, minus any measurable or even hinted-at impacts of today’s reduced levels of menhaden harvesting on sports fishing, and looking at a valuable fishery being accomplished at what is undoubtedly a sustainable level when considered in any kind of historical context, why the concern with commercial menhaden harvesting? With every “new” anti-commercial fishing campaign it seems more apparent that there is an ongoing movement to reserve our coastal waters - and our fisheries resources - for the exclusive use of a small group of privileged sportsfishermen and yachtsmen. These people, who are fortunate enough to be able to spend tens of thousands of dollars and upwards - sometimes upwards into the stratosphere - on their sports fishing boats apparently don’t want their hobby or “their” ocean cluttered up with working fishermen, fishermen who have the gall to want to catch the same fish or use the same piece of water that they do - and then to want to share their harvest with the public. The professional fisheries managers have heard all of the anti-commercial crowd’s specious and self-serving arguments before and, having the science at hand to refute them, aren’t swayed. That’s probably why legislation is now the anti-commercial fishing tool of choice. But postcards and constituent complaints don’t alter fifty years of data and won’t make unjustified restrictions on working fishermen - or on the businesses they support or the markets they supply - any more acceptable. We have an expensive and increasingly effective fisheries management system based on real science. Don’t we owe it to the entire public to let it work the way it should?

| For more information on the menhaden fishery contact Niels Moore at the National Fisheries Institute (703-524-8884) Judy Widerstrom at The Mid-Atlantic Fisheries Gazette (609-898-9452) or Nils Stolpe at NJ FishNet (215-345-4790) |